I want to start with expressing my gratitude to all of you for joining hands with us today. For your calls and emails and texts. We need you now, and we will need you in the coming days and months. Your fond memories... your ears... and your shoulders.

I am in the habit of speaking at events and I had intended to speak at this one. But something happened on the way to the memorial service...

I don’t want to be on a stage. I don’t want to lead anything.

As the firstborn in a fractured family, I was often asked by my parents to BE a parent.

To my siblings. And to myself.

On this day, I just want to be a son.

A son and a father who is crying. A son and a father who knows how to hold down the fort but who doesn’t really know how to let it fall apart for a time.

It has fallen apart for THIS time.

So I have asked my brother-from-another-mother to read my words. I can’t speak them right now. But I want you to hear them. I want my mother to hear them. And I want to be able to weep at the same time.

This is the only way to do both.

***

My mother and I met on August 2nd, 1966. She was present at my birth, naturally. But she was not conscious. An emergency C-section denied her that moment. And when she awoke from the sedation, I was not there. She did not know if I had survived the umbilical cord wrapped and tightening around my neck as I made my way down the birth canal.

She did not see me take my first breath.

But I saw her take her last.

My mother’s last breaths were labored. Hard to watch. She fought so hard. And this was her nature.

You may not know this -- how much of a fighter she was.

If there was one word that you all used over the past few days in remembering her, it was “Quiet.”

Not “quiet” as in mute or speechless, but “quiet” as in “quiet love”.

One old friend of mine who has not seen my mother for at least 30 years said on Facebook: “I remember your mom as gentle, and with a calm stillness.”

Someone I never met wrote: “She had a quiet grace and beautiful presence.”

This impression lasted. And it is so true. She was quiet.

But she was also a badass.

When I introduced her in my memoir, I didn’t use “quiet” at all. I described her this way:

Mama is brilliant: a computer programmer taking a break to stay home with my baby brother but never not working. She’s comfortable around a jigsaw, handy with a slide rule. In other words, she’s not your average Chestnut Street lady.

That was my earliest impression of my mother, and my last.

My mother was quiet in the sense that she spoke more with her HANDS and DEEDS than with her words. She cooked and baked and braised and steamed and sautéed her love for us.

She picked kiwifruit for us from the kiwi vines she grew... on the arbor she designed... and delivered them in the baskets she weaved.

This is the first memory of my mother which I share in my book:

“It was Amanda’s birthday, and we were camping, partway into a three- month cross- country drive from Marblehead to Mexico... She turned four in the Everglades. I was six and a half. Papa took us for a walk to look for alligators and when we came back, there was Mama, emerging from the big canvas tent with a double-decker strawberry shortcake. Whipped cream and berries on top. Even candles. No sign of an oven. No campsite refrigerator.

But that was Mama, always creating something from nothing.

“That was amazing,” Amanda says through the fingers in her

mouth.

“That was,” I say.

***

That was.

When my mother did speak with her voice, it was usually in song.

Her love of singing led her to the Brookline Chorus, to Makhela, and...

Some of you were at the rehearsal dinner the evening before Dana and I were married and may remember this: My mother was asked if she wanted to speak and she said “I’m not good with words, but I can sing.”

What she didn’t know was that the dinner was held in a private room adjacent to a large dining hall and there were no doors to close -- no way to drown out the din of Lola’s raucous cajun restaurant.

That didn’t stop her from launching into an a cappella rendition of “First Born” by Kate and Anna McGarrigle.

I will never forget the sound of her voice, resilient despite it all. We couldn’t hear her words, but we could feel the message.

***

My mother endured many hardships while parenting me:

When I was 7 she gave me the Heimlich maneuver because I tried to swallow an entire canned peach half.

She sat through The Blue Lagoon with me at the Danvers Cineplex because I was in love with Brooke Shields.

She weathered the smoking, drinking, drugging and debauchery of my teenage years. (Sort of. She kicked me out, eventually. But I would have kicked me out sooner.)

She also gave me so much:

She helped me with a downpayment for my first house.

She moved to Northampton to be a consistent part of helping us raise her grandchildren, and she was an active and engaged Bubbe.

She welcomed and loved Dana like a daughter.

And she gave us 31 years of borrowed time:

Mom was hospitalized in Boston in 1993. She was 51 and was experiencing sudden and unexplained liver failure. I remember vividly the transplant surgeon who came to evaluate her that night. He was kind and gentle. He said:

“Phyllis, I’m doctor Jenkins. I understand you are a mathematician.”

“Oh yes,” she replied.

“Can you count backward from 100 by 7s for me?” He asked.

“Of course,” she began. “100... Ninety.... Ninety...???”

He took me out of the room and told me “your mother has a 20% chance of surviving this weekend. The only thing we have going for us is that she has a very rare blood type and if an organ were to become available, she is probably the only person on the Eastern seaboard who could use it."

That was Friday evening, Fourth of July weekend. Holiday weekends tend to have a high mortality rate, and mom overcame some very low odds.

Recovering from a liver transplant in 1993 was no joke. She spent the next three months in the hospital, fighting her way back. Her resilience allowed her to get back on her feet, remarry, see her three children married, redefine her career in a way that allowed her to travel the world, see four grandchildren come into that world, see three of them graduate high school, one graduate college, and the youngest be enrolled in preschool.

And while the theme here is one of feminine independence, I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge the three decades she spent with you, Rich. You provided her with companionship, intellectual parity (no small feat), and a love of art, music, and travel. I owe you a debt of gratitude for the love and commitment you showed her.

***

My mother was effectively frugal, and that frugality enabled her to help all four grandchildren with their college educations.

In keeping with her "quiet nature" we didn't even know she was capable of doing such a thing until she told us in 2020 when Sam, her oldest grandchild, was enrolled at UMass.

She was so proud of you, Sam, Sylvie and Zachary. She wanted you to have the thing she valued second only to family: a college education. That you all took her up on the offer was the greatest gift you could give in return.

Kingston: she was absolutely smitten with you. In recent days, I only heard her utter one regret, and that was you would not have the chance to get to know her better, and she you.

When my mom attended Sam’s graduation in May we knew things were bad.

I often called our other brother-from-another-mother, Dave Feinbloom, who the family refers to as Doctor Dave, and I asked him for advice as the emergency room visits and hospital stays increased.

Dave said: “if you had told me 20 years ago that we would be discussing an 82 year old patient who was 31 years past a liver transplant, who underwent spinal surgery as the pandemic was unfolding, and who is on nightly peritoneal dialysis....? I’d say you were crazy.”

Mom loved you.... AND loved having a Beth Israel hospitalist in her rolodex. Thank you, Dave.

But you forgot to mention the two new knees and two new hips.

Remember? That's why we called her Bionic Bubbe.

For a time, she used to sit at the front desk here in this very building greeting visitors as a docent. They saw a little old lady. She quit because it made her feel like a little old lady!

Maybe you saw a little old lady, too.

But now you know: that lady was a badass.

She probably wouldn't like me repeating badass in a eulogy. My mother-in-law, Carol, visited her in hospice and came away, saying that my mother reminded her of a proper, dignified lady in a BBC show.

I shared that with mom, Carol, and she liked it very much. She said that her mother had taught her well.

What I don’t know is who taught my mom to fight so hard. What I witnessed her endure over the past year was especially harrowing. I can’t imagine doing it.

We could all see where it was headed, and yet as recently as September, she was entertaining the idea of moving out of the assisted living facility and building a “granny pod” in our backyard.

One of the last emails we received from her was on September 21. It was a design for an Accessory Dwelling Unit from a company in Colorado. She wrote:

I am really interested in this design. The company seems to have a complete process from planning to constructions, even though they are in Colorado. I would like to set up a virtual consult with them. Are any of you interested in joining in? If so I will try to plan it at a time all can be there.

Mom

For those of you who saw her in recent months, you're probably thinking she was crazy.

WE THOUGHT SHE WAS CRAZY.

But what she was was a fighter.

She was a woman who took her life in her own hands. A woman who could send an email like that on September 21 and then, on October 10, decide it was time to end her life.

She never questioned her decision once she made it.

A fighter, yes. A problem-solver, always. But ultimately , and always, she was a pragmatist.

For those who don’t know about peritoneal dialysis, may you never know. But it is worth sharing that in order to do this procedure you need a port surgically implanted in your abdomen, very close, it turns out, to your navel.

It is not an exaggeration to say that this was an umbilical cord for my mother in the last year of her life. To separate that cord from the machine that sat by her bed for any real length of time was to die. It might take days. It might take a few weeks. But it would unquestionably, irrevocably happen.

So, in true Phyllis fashion, she scheduled the end as best she could:

She would leave the hospital on Monday to begin hospice but stay on dialysis until my brother David and my nephew Kingston could come to say goodbye. They would stay Thursday through Saturday and she would do her last dialysis on Friday night, knowing that her cognition would likely begin to decline Saturday evening.

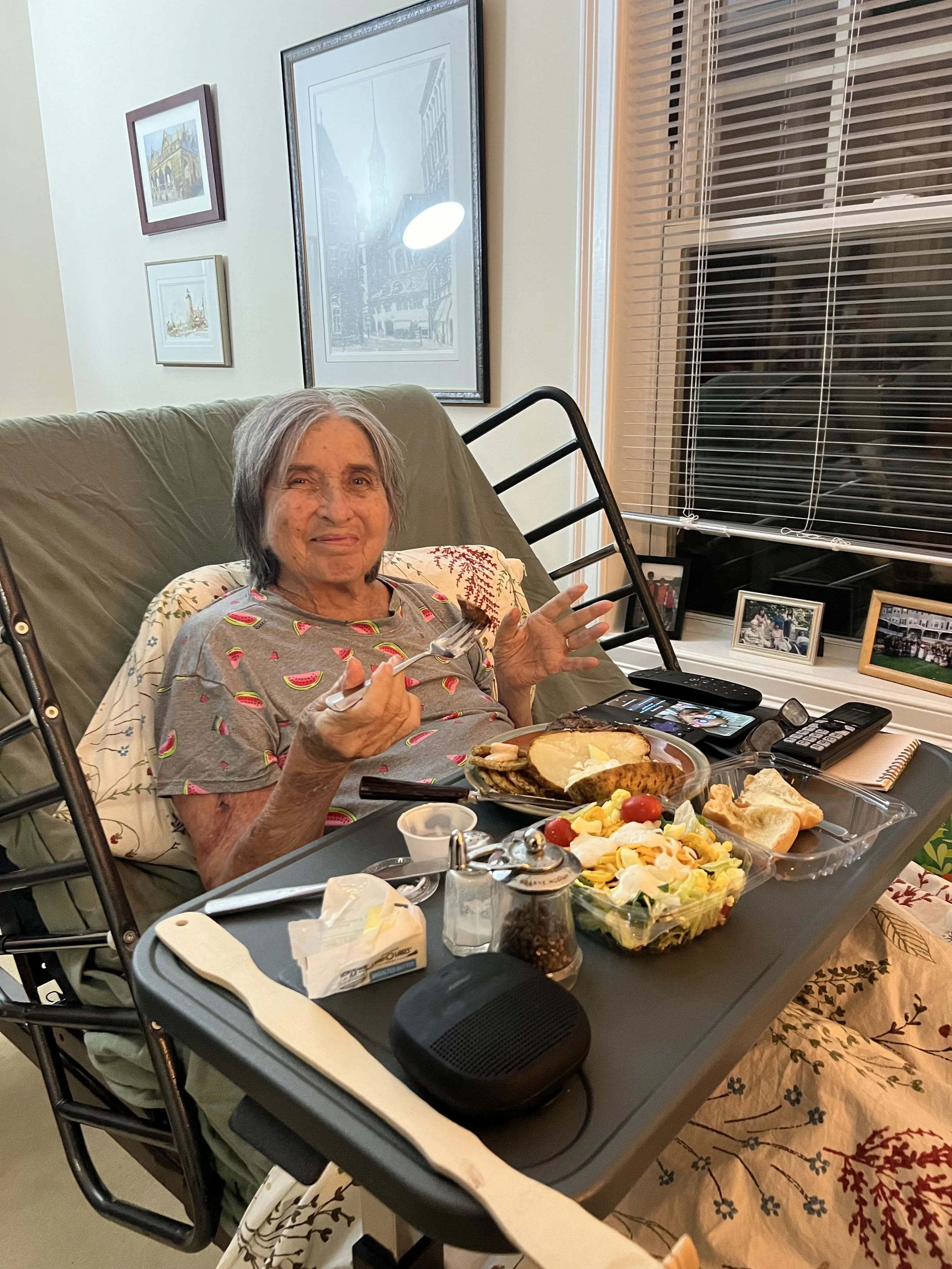

She wanted a steak and baked potato dinner for Thursday night and a vegetable lasagna from Mulino’s on Friday. When I tried to get the lasagna from Pasta Y Basta in Amherst instead because it was closer than driving to Northampton on a busy Friday night, she balked.

And she ate it all with gusto.

As if she were knitting a sweater or building a bookshelf, she mapped out a process that allowed her the opportunity to see or speak with just about everyone in her life who mattered to her.

She got to say goodbye.

I heard her say it again and again. The phone would ring, and she would say “Oh, Hi Linda. Well, no I have some bad news. I’ve decided to end my life.”

It was so hard to hear, but also so honest and real.

For a person who was “not good with words” my mother found them in the end. But unlike ginger or garlic, she did not mince them.

As my friend Lisa, also a doctor, said to me before the decision to go into hospice: “These days most Americans die surrounded by machines and strangers.”

My mother died surrounded by loved ones.

That doesn’t happen to people who have not loved hard and well. It may have been quiet love, but it was fierce.

And no one was with her for more of her final hours, for more candid conversations, for more middle of the night emergencies, than my sister Amanda.

AMANDA: you are our mother’s daughter in the way that was most important to her. You are a rock. A strong, self-possessed and independent woman. She leaned on you so much in the end, but she wouldn’t have if she didn’t believe in your loving strength.

I only saw my mother cry a few times in the final days. She cried hardest when she realized she could no longer care for herself. It was the greatest pain for her -- the idea that she had finally lost her hard-fought independence.

She asked if there was a way to make things go more quickly, then thought better of it and said “I guess I don’t want to play God.”

But you know what? I think she did.

A woman who overcame so much adversity.

A woman who built a family against innumerable odds.

A woman who would do it, whatever it was, if she decided it needed doing.

A woman who grew up kosher but lived a secular life.

A woman who didn’t believe in God.

Why NOT her?

That was my mom.

Hers was a quiet love but her absence does not feel quiet. There’s a cacophony where there once was a mother, sister, Bubbe, friend.

In the last hour of her life, Amanda, Dana and I played her some Chet Baker. She loved Chet.

It was a mix of songs: some trumpet playing, some crooning.

She died listening to Chet play.

A few minutes after, as we lay over her body and wept, Chet began to sing.

I’ll leave you with the song that played as we wept, and laughed, and wept, and laughed, and wept...